Ben Wheatley is one of my favorite directors working today. His filmography is a varied and fascinating mix of genres, styles, and budgets that makes for great pub quiz questions. Who else would go from a Netflix adaptation of Rebecca to the low-budget sci-fi horror In the Earth and then to directing Jason Statham in the summer blockbuster Meg 2: The Trench in a span of just three years?

Wheatley came to visit Helsinki for the Night Visions International Film Festival with his producer, Andy Starke, who is the co-founder their production company Rook Films. Together, they've made films like Kill List, Free Fire, and A Field in England.

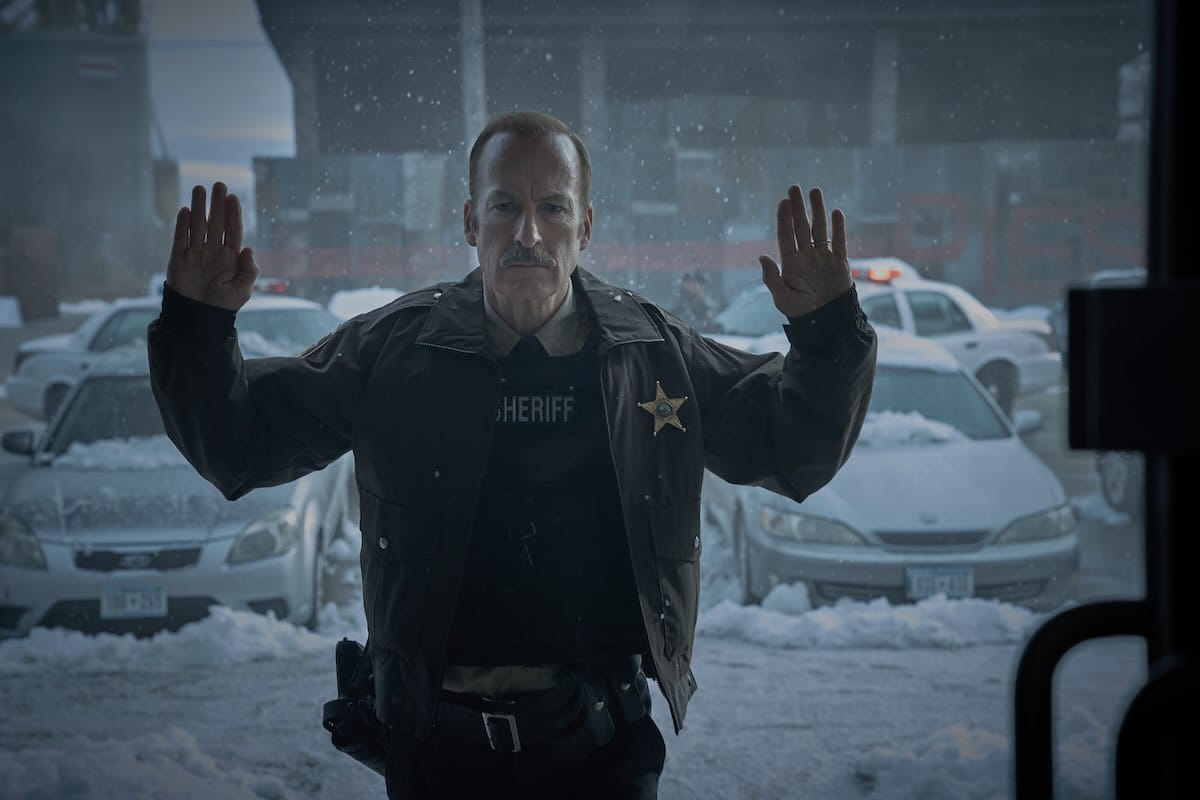

This year, Wheatley has two new features under his belt. Normal is a big popcorn actioner starring Bob Odenkirk in his dadsploitation era while Bulk is a micro-budget time travel film about a society losing grasp of reality. Once again, he's hard to pin down.

During my hour with the duo, we spoke about working in the industry today, mellowing out with age, and how Free Fire is one of the most underrated action thrillers of the past couple of decades.

This interview is edited and condensed for clarity.

Is there a big difference in the feeling of making a big studio film and making something on a smaller scale?

Ben Wheatley: I think it's the difference between making films that you've written and the films you haven't. It's not about the money necessarily.

If you're not fully authoring it and also not in control of the production then it's a very, very different experience to when you are. So a film that Andy and I make together, there's much more control. But if I'm off doing a studio picture, then I'm part of a much bigger team of people collaborating on making something. It's about where you are in the triangle of production.

Is it harder to feel more connected to the material if it's somebody else's script, or do you still find a way to connect with it?

Wheatley: When I thought about filmmaking as a kid, I looked at it from the perspective of the studio directors of the 40s and 50s. It looked like this really amazing job where you would go from genre to genre and different types of movies within the studio. I've always wanted to do that. But on the other hand there's the more French auteur version of indie filmmaking, where you're authoring stuff fully.

So I go between those two positions. You find different ways through the material. It doesn't mean that I'm not as committed to each of the different types of films that I'm doing.

I want to ask Andy: You've worked together with Ben for a long time, what makes a good producer?

Andy Starke: I don't know. I've never worked with one.

Wheatley: No, I have!

[They laugh]

Starke: I mean, it's interesting. It's my moment of staring in the mirror. Because it's very easy to talk about films. Lots of people talk about making films, and there's a world of film where the actual film is kind of irrelevant.

A good producer on one hand is someone who can find the money to make a film. It's pretty basic. But I would also say a good producer is someone who supports the people who help the director to make the film they want to make.

When we're talking low-budget indie films, I believe they should be unique, personal, and provocative. They're a totally different when you're not staring at a huge budget. I'm not trying to make my film, I'm trying to help the director make their film.

When we started, I was the producer because I wasn't the director or the actor. Then we did Sightseers with Nira Park, who produces Edgar Wright's films, and I really learned from that.

It's just pushing projects forward, and as soon as somebody says maybe we'll give you the money, you go: Great, we've got the money, we're starting next week, lovely.

Then you have this terrible moment when you have to throw it off a cliff and start the film or else it will never happen because people just talk and talk. There's a lot of people that just want to talk and not actually do it. And I think that's the really interesting period when the film is hurtling off the cliff and you're hoping God or someone comes to save you.

I think ultimately it's trying to understand the whole process, which is why we've got a distribution company. As soon as I realised how you physically put a film in a cinema, like getting a DCP from a hard drive onto a screen, and how that's really easy and cheap, it became not just about making the film, but releasing them and understanding all of that as well.

Wheatley: We've been around long enough to see the full life span of a film, including when the distributors have to relinquish the rights back to us and going: "Why did we do that? Why did we let them have it for so long? Is there another model where we don't let them have it for 10 years?"

I think you can probably make that mistake twice, but if you make it three times, it's probably bad.

How has the landscape changed for that? Is it now easier to hold on to your stuff? Is it harder?

Wheatley: Basically every film we made the landscape has changed dramatically. It never sits still for a minute.

It used to be there was a minimum guarantee and they'd give you like a chunk of cash, like 50 to 100 grand or something like that, which they don't do anymore. Instead, they just take your film, then they'll account for it in terms of their expenses of trying to put it out, and then they put that money against the film. And it's unlikely to make that much money in the theatrical run anyway.

So then your film's got a load of debt, then they plug it on to the streamers and keep all that money, after which they keep it for 10 years. So you never see any more money from it.

So we thought if we do our bit and keep the budget lower and then we tour and distribute it ourselves, it makes much more sense. That way we keep it and it's an asset for us rather than giving that away.

I think that's the bit that started to change. But the whole thing was always based on an old business model of selling DVDs, back when they still sold loads of copies.

Starke: You've got a fundamental problem which is that films cost too much to make. Well, they cost more than they're worth.

If you make a television show and you get a commission and there's a cost associated with that, then that's what it's worth to the television channel. So it's paid for. Then there's a second tier of money which might be selling it to other territories and all that sort of stuff. But with an indie film, you just have to sell it. If you're a sales agent at a major film festival you're giving films to people for nothing, which is kind of crazy.

So how do you solve that problem is the problem.

One of the biggest learning experiences for me was back at the film market in Cannes where you can actually see the business side of everything.

Starke: It's terrifying, isn't it? It's about two meters from the red carpet vertically to the basement below the Palais where there's thousands and thousands of films that someone is trying to sell.

Wheatley: As filmmakers, we look at every aspect of what we're doing. It's from writing all the way up to distribution. You have to keep looking at how it works and to work out ways of doing it better. Because you can't just rely on others. Everybody has their own way of doing it that earns them money, and they don't really want to relinquish that back to you.

Starke: It's really easy to feel very negative about it. You just have to believe in the stuff you want to make. But the good news is that people are always looking for interesting stuff, I think. There's always things that break out that are completely not what you're supposed to be doing. I don't think it's all doom and gloom. It's difficult, but then what isn't difficult?

But I think if you can create something that's unique, interesting, provocative, whatever, there's an audience for it.

Wheatley: That's what's so hysterical about all this AI crap. Because the whole thing is predicated on making original, novel entertainment where people will say: 'Oh my God, I've never seen that!', and you're going to do that by taking software that looks at all of cinema and copies it? It's not going to work. It's just going to be boring.

Starke: It's a useful tool to automate tasks that were very boring before. But the reality of creation with it is just rubbish, isn't it?

Wheatley: The stuff where it's helping your grammar doesn't hurt you. But I think they wish they could automate Hollywood and just have a creative spreadsheet that would then just pump stuff out that made money and go around the artists because they don't want to deal with them.

Speaking of something that's original, I want to ask about Free Fire, because it's one of my favorite films of all time.

[Both Starke and Wheatley pause, look at each other, then look back at me.]

Wheatley: You should have led with that!

[They laugh]

It's the first action film where I could understand the geography of it all pretty much instantly. Being autistic, I have a hard time sometimes capturing the where and how and why of things. So I want to start with: where do you begin when staging an action sequence to tell a story?

Wheatley: I was thinking a lot how action can be a series of small stories. So it's like a story of how I knock over the glass and then I catch it and then I smack someone around with it. The cause and effect of it all. That's why these characters all these tiny little goals they had to do.

It was a reaction to scenes in big Hollywood movies where lots of things were blowing up and the stakes were enormous because you can destroy the world or the galaxy and blah, blah, blah. But each time I'd see that it didn't relate to me on a human scale. So it was turning action to a more human scale and making it as small as possible. It was about hurting your hands or getting burnt or getting dust in your eyes. It was reducing it right down.

I also thought about Evil Dead 2 and Tom & Jerry and the Warner Brothers cartoons which all have that Rube Goldberg kind of stuff.

The other thing was that I found a transcript of an actual shootout that had happened in Miami between the FBI and bank robbers.

The FBI had intercepted the robbers on the way to the bank and they had a shootout between the cars where they staggered out of the cars and shot at each other and it went on for like 8-9 minutes. They were shooting everywhere and people were missing at point blank, and I just went, that's not what it looks like in movies. I thought it was interesting what you can and can't do under pressure.

We used visual planning to make the script work because it was in real-time. You could get disoriented really quickly if you didn't have a strong sense of geography because decisions you make in the first minutes find the characters all in the wrong places for the things you'll need them to do at minute 60.

So it was planned like that, and then we built it in Minecraft.

I'm sorry, Minecraft?

Wheatley: Andy's son built it, in fact.

I sketched it out and he filled it in, but it was so that we were all logged on and we could walk around the space together and talk on the phone as we were doing it. That way people got an idea of what the geography was.

After that, we got cardboard boxes which were the same dimensions as the Minecraft cubes and we when we got to the location we put those boxes in where the set was going to be. That way we could look at all the angles and all the action blocking to make sure that it all worked, so there was a series of checks to make sure we didn't fuck it up.

Then in the end, when I sat down with Patrick Smith, our designer, he had what he needed to do; how high the walls were and where the pillars were and all those things.

We built maps between us to show where the characters would be at any one time so that they didn't go into the wrong places.

But it's interesting how you felt that you understood the geography, because the criticism of Free Fire is that people don't understand it.

I read some of the reviews it just feels baffling. To me this is the first time an action movie works in not just the visuals and the way that it's built, but even how the sound cues tell you everything.

Wheatley: Yeah, that's what we thought as well, but what it tells me is that people understand the visual stuff really differently. I mean, you know how people ask: Can you see in your mind's eye? Can you visualize a cube? Can you visualize 2 cubes?

I can.

Wheatley: And can you rotate them around and see them in your mind's eye?

Yeah.

Wheatley: Well, I can't.

Starke: I can't curl my tongue.

Wheatley: My wife can do it. She can spin the cube and it can spin for ages. My mind just glitches and I can't see it.

So I think that people have very different experiences of the world of how they fundamentally see it. The reaction was so polarized because there's a split between people who could understand and people who couldn't.

This is kind of what testing a film is for. Sometimes you get this stuff in movies where the characters say: "Get the red bag and give it to Jim", and then you get the notes back from the screening that say: "They don't know who Jim is or what's in the red bag."

And you're just: For fucks sake, they said it out loud, why don’t they understand it? Then you look back in the film and try and work that out, because it should be so fucking clear, but it always isn't and there's loads of things that can stop that from happening. That's part of the calibration of movies.

But with Free Fire, there was no fixing it once we had done it. We couldn't make it any clearer, I don't think.

For me, it had the same kind of almost mathematical certainty to the action like a Jackie Chan movie, where they show you in advance where their fight is going through just visual cues. Here, it was with the sound and how the ricochets would switch channels to tell you this is where we are.

Wheatley: It's like music. It's all about rhythms and the drumming and then in comes the percussion and that's why the actual music of the film is like that, too.

Starke: There's a lot of a lot went into the sound. A lot of it was all bespoke.

Wheatley: Every noise and ricochet is different and a lot of them are recorded in rifle ranges with bullets flying over mics. But the funniest trick of it is that the film itself gets quieter. It starts really loud with the music and then it goes quieter and quieter and quieter until they fire the first gun and then [the sound] goes back up to where it was. But perceptively you're like, God, this is really loud, but it's not; you've been straining to listen.

I did have a question about Bulk. This has been a busy year for you. You've had Normal and Bulk and they couldn't be more different from each other. Where did the latter come from? When did you realize that this is something you wanted to work on?

Wheatley: It's a weird one because it kind of materialized out of having time to make a film.

I was talking to Sam Riley and Alexandra Lara all year saying it would be good to make something with them. I kept thinking how Sam looked like Alain Delon or Jean-Paul Belmondo and that led to the freedom of French New Wave movies. Also, I had written a graphic novel the year before and that got me thinking about comic book writing and how free it was. I wanted to do something that was free and elastic, so it started to bubble up from that.

But it was also about the general state of things in terms of how narrative is used in everyday life. Going from the position of being a professional storyteller to seeing the technology used against the population in many different ways, I started to think if there is a way of unpacking this madness or the feeling of these different narratives all competing with each other, and how do we move towards something that isn't just a mad circle.

There's no easy answer to that question, unfortunately. There was no AHA-moment and I didn't just sit down and write something like this. It's been coming since I was a student, because I used to write comic books that delved into metaphors and characters that knew they were inside fictional spaces. I've been thinking about it for years.

Andy, when Ben came around with Bulk, what was your reaction to that? It doesn't seem like the most easily approachable thing.

Starke: Oh, we've gone beyond that. That's never an issue. But that's why it's not an expensive film. There's a logic behind that. We produce it together so it's not a film people are going to spend millions of dollars marketing. It's playing the long game. It's made for a price that makes sense, which allows us to play and be free.

I think the most successful thing about Bulk is it kind of makes most of its budget. The plot is literally about nothing being real and everything is seen from different perspectives, even to the point where the cameras we shot it on are kind of degraded or different. I thought that was really interesting how it's not just a film where you get rid of everything and you have a white room with two people in it. Instead it's: 'Why don't we have a desert or a storm?'

I think it allows you to play around with it. I think some people are kind of cross with it narratively, but on some level I like films that provoke and challenge viewers.

Wheatley: It depends on what your diet of films is. Compared to Tarkovski, Bolt's quite calm and sensible.

I also really like the part in the credits where it almost feels like they're talking back at the viewer. They keep you on your toes all the way to the end.

Wheatley: There's a bit of communication that I always felt was lost on other films. I didn't want to do post-credit sequences or stuff like that because it's all been done before. This was more an opportunity to talk to the audience in a different way and say: 'This is how you can make your own film. You should do it if you're interested in it. It's not as hard as everyone goes on. The technical side of it is there for you'.

Obviously, I don't say the really hard bit is writing the stuff or making something interesting. That is hard. But the actual bits and bobs of the physical making of it are available.

It's a really nice and inspiring thing to hear. It's important to repeat for people like myself who want to exist as creatives. Just to have a reminder that it is possible.

Wheatley: I'd always read biographies and stuff about filmmakers, but I'm only interested in the first three chapters. I'm not interested in their success. You want to see how things get put together.

As a filmmaker, no one ever told me anything about how it worked. It's better now because YouTube has quite a lot of essays and you can find out stuff. But when I was younger, there was nothing there, there was no information. So I think the main thing I learned is that you don't need to ask permission. You just do it. It took a pretty long time to learn, so if I can help by saying just do it, I will.

Starke: You have to have a level of self-belief. Everyone just wants to say no. So you just go, okay, well, we'll just do it ourselves. That's what happened to us.

I always say, if you could put the energy that it takes for you to be rejected into doing something, you could rule the world. It's really tiring being told to fuck off. It's exhausting. But you can't just sit there and go, why doesn't anyone believe in me? You've got to show them. And pretty much everyone I've worked with who's made a film has got to make another film. They've all gone out there and done it. It's almost easier to go and make a low-budget, interesting film, than it is to try and get money to make a bigger budget film on some level. Well, easy is not the right word, but you know what I mean?

Wheatley: Less hard.

One last thing I wanted to ask about is Normal.

Wheatley: Did you see it already?

I got a chance to see it at the Toronto Film Festival. The audience responded really well to it there.

Wheatley: Yeah, they were really excited about it.

It ties back into Kill List a bit. That's an almost, I don't know if it's the right word, but a mean movie. Compare that to Free Fire and now Normal, would it be fair to say you've gotten kinder as a filmmaker over the years?

Wheatley: Consciously, yes.

After Kill List, I was like, this is too dark. I think it's kind of easy for me to be dark and I felt it was lazy that if I have an opportunity to talk to audiences, why am I doing this to them?

Normal is that crowd-pleasing movie where you push and punish the characters, then when they snap and come back the audience is on their side. We were very conscious about how empathetic Bob Odenkirk's character was going to be and how he worries and cares about the people in the town even when he's fighting them. It's not like he's taking bloody revenge on them all. It's more like, 'I'm in this terrible situation, can I survive it with killing the minimum amount of people as possible?'

I think that was what interested me in the project and how it's a kind of spiritual cousin to Free Fire in many ways. I think I got the job because of Free Fire to be honest.

It has that same sense of Ruth Goldbergian scale of cause and effect we talked about. How things just fall apart, and you know they're going to, so it becomes this really exciting game of waiting to see how it happens.

Wheatley: Normal's like an action movie, but it's also like a public announcement about being careful. There's so many just random things that happen to people in it. Things drop on them, stuff explodes. It's a dangerous world.